After delving into the T/F and the triplets questions, it’s time to tackle the recipe question.

This one can be tough for judges who are unfamiliar with recipe design and have not experienced the brewing process firsthand. Fortunately for me, I had homebrewed more than 120 batches at the time of the written exam and had been releasing recipes on this blog for several years.

Nonetheless, it needed considerable planning and memory exercises to tackle down all the 12 recipes of the exam pool.

To learn more about the Written Exam structure, please read here.

To learn more about the T/F questions, please read here.

To learn more about the Triplets question, pleas read here.

The recipe question

This question consists of four parts:

- Describe the style (no numbers are needed). 15% of the total score

- Provide the recipe’s target parameters. 15% of the total score

- List all the ingredients (with weights and rationals). 40% of the total score

- Discuss the complete brewing procedure. 30% of the total score

The recipes are taken from a pool of 12, listed on the official BJCP website (link). These styles you should already know perfectly as part of the strategy to tackle the Styles Triplets question, discussed in a previous post.

This is a difficult question for people who are unfamiliar with the recipe design process. Some may find it easier to skip all of the math that I will describe in the following paragraphs and simply learn the ingredient quantities by heart. That would be a viable alternative, but it wasn’t the case for me. I already had a lot of information to remember for the styles questions, there just wasn’t enough room left in my head.

I am a homebrewer. I design beer recipes on a daily basis using software that does the math for me. I just had to find a way to do the basic calculations on paper; the recipes would come from my experience in brewing.

I trained myself to answer the entire question in 20 minutes, using a calculator to obtain the correct numbers. Try to use no more than two pages (two and a half tops) for your answer.

Memorizing recipes numbers

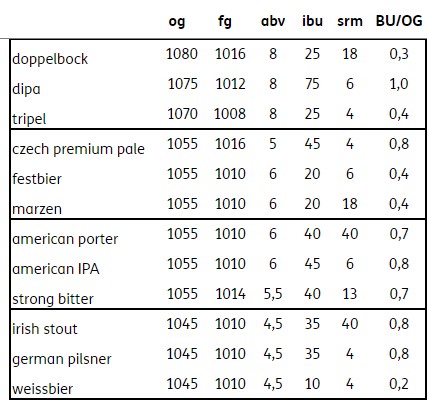

The first step is to write down the recipe’s statistics and memorize them. I didn’t want to memorize too much info, so I organized the OG, IBU, and other numbers into groups. The end result is the table shown below.

To make it easier to remember the numbers, the 12 recipes can be organized by OG, ABV, and SRM. Six out of twelve recipes have an OG of 1.055, three have an OG of 1.045, and three have OGs of 1.080, 1.075, and 1.070, all of which are 0.005 points apart.

To make it easier to remember the numbers, the 12 recipes can be organized by OG, ABV, and SRM. Six out of twelve recipes have an OG of 1.055, three have an OG of 1.045, and three have OGs of 1.080, 1.075, and 1.070, all of which are 0.005 points apart.

A similar approach can be used to categorize ABVs and FGs, with a few easy-to-remember exceptions, such as Czech Premium Pale Lager (less attenuated, lower ABV) or Double IPA and Belgian Tripel, which have more attenuation and a higher ABV with a lower OG.

Grouping the beer by SRM yields five categories that are rather easy to remember.

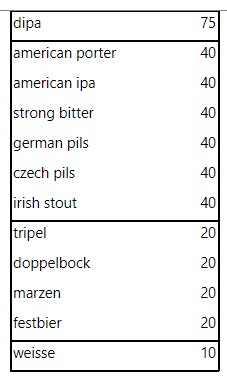

Grouping by IBU produces four groups:

The recipes

Any of these 12 beers can be brewed with three malts or fewer. There is no need to write elaborate malt bills. Keep hop additions basic, with one at 60 minutes, one at 5 minutes, and one in dry hopping if necessary. The Double IPA could benefit from additional hops at 15 minutes, but it is the only exception.

Most recipes call for Chico strain yeast, whereas the lagers all use the same W34/70 yeast, with the exception of the Czech, which prefers Bohemian Lager yeast. The Belgian Tripel, Weisse, and Strong Bitter may all be made with these three yeast strains: Belgian High Gravity, Weihenstephan Weizen, and London Ale I.

Reliable sources for recipes include the American Homebrewers Association website with medal-winning recipes and Zainasheff and Palmer’s recipes book. You can also consult my Homebrew To Style recipes handbook, to which I add new recipes each month.

This blog contains recipes for ten of the twelve exam beers; links to each are provided below:

- Double IPA

- American Porter

- American IPA

- Strong Bitter (you can boost the Best Bitter recipe I provided)

- German Pils

- Czech Pils

- Irish Stout

- Belgian Tripel

- Doppelbock

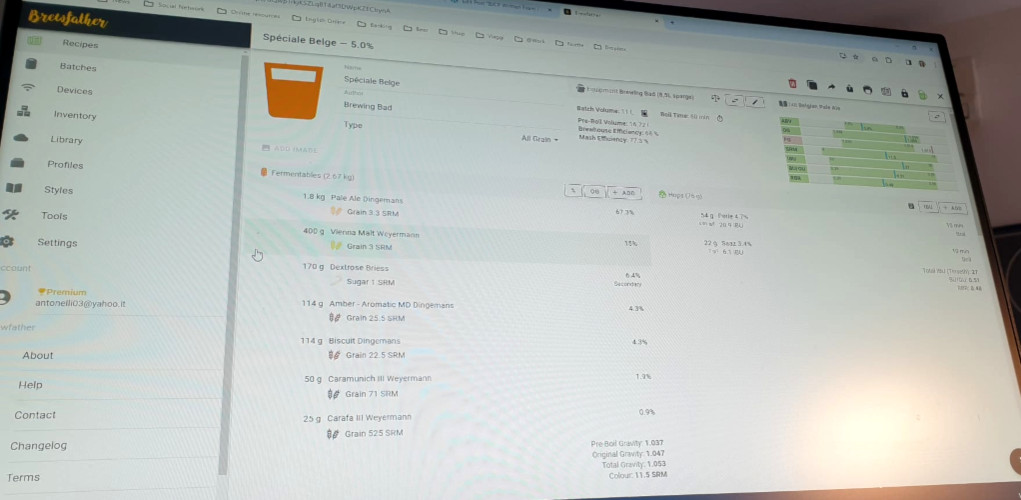

Keep the recipes as simple as possible, paying special attention to using the right malts and hops and achieving the ideal parameters. My recommendation is to use recipe software such as Brewfather to ensure that all of the parameters for the 12 recipes are accurate.

How to calculate malt quantities

Instead of memorizing weights, I chose to use percentages versus the total grist. So, for example, a Weissbier grist is 50% Pilsner and 50% Malted Wheat. There is no wrong recipe as long as you use the main ingredients of the style in the right percentage range.

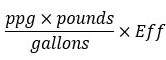

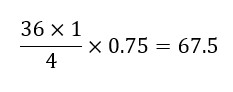

Once you have memorized each style’s statistics and grain proportions, quantities must be calculated. The formula to calculate how each malt contributes to the overall recipe in terms of Gravity Points which add up to the OG (Original Gravitiy) is the following:

where ppg is the malt potential (Pounds Per Gallon) and Eff is the brewhouse efficiency. 10 pounds of a classic base malt with a 1.036 ppg potential used in a typical 4 gallons batch with 75% efficiency will contribute 67.5 Gravity Points.

In other words, a 4 gallons batch made with 10 pounds of this malt in a 75% efficiency brewhouse will produce a 1.068 OG beer.

Doing this calculation during the exam would be extremely overwhelming, even with a calculator (which can be used). With a bit of approximation, the formulas can be adjusted to our needs. I’ll talk in metric units now, but the same reasoning can be applied to US metrics.

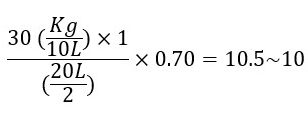

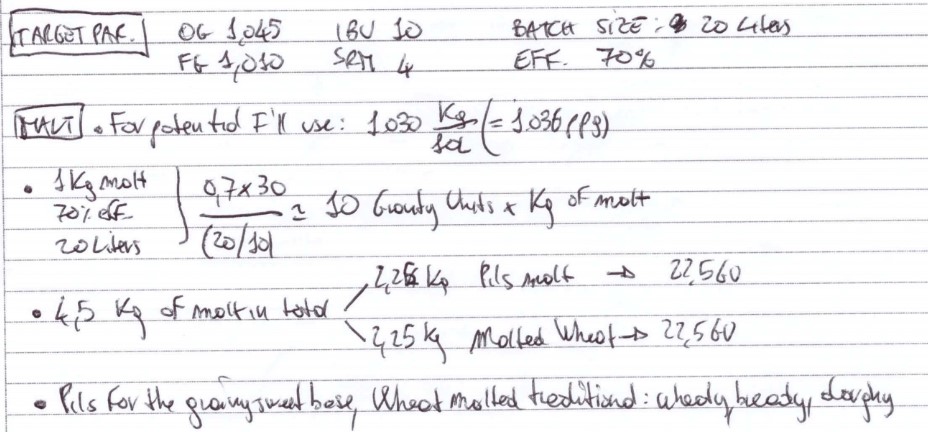

Before you begin the calculations, state that you will use 1.030 Kg/10L (1.036 ppg) as the potential for all malts in your recipe (this is a reasonable approximation).

The batch size would be 20L and the system efficiency 70%. Using this numbers, 1 Kg of every malt will contribuite circa 10 Gravity Points to the recipe.

Let’s come back to the weissbier recipe. We know that the OG should be 1.045 and the recipe calls for 50% Pilsner malt and 50% malted wheat. We’ll need 45/10 = 4.5 Kg of malt in total, of which 4.5/2 = 2.25 Kg Pilsner malt and 2.25 Kg Wheat Malt.

Let’s come back to the weissbier recipe. We know that the OG should be 1.045 and the recipe calls for 50% Pilsner malt and 50% malted wheat. We’ll need 45/10 = 4.5 Kg of malt in total, of which 4.5/2 = 2.25 Kg Pilsner malt and 2.25 Kg Wheat Malt.

That’s pretty much it.

With a calculator on hand, once you memorize the percentages, calculations can be done in seconds. The only caveat is simple sugars, which have a higher potential of 1.046 ppg and are converted at 100% efficiency.

Adding simple sugars is mandatory in the Belgian Tripel recipe and optional in the Double IPA. Using the formula above with 1.038 Kg/10L potential and 100% efficiency, we get that 1 Kg of sugar contribute 20 Gravity Points to the recipe.

Easy-peasy.

Here is my answer to the malt part of the recipe question. I was asked to write a Weissbier recipe. I brewed the style only once in my life, but the recipe is really straightforward. Don’t forget to add a few extra words to explain why you are using such malts.

How to calculate hops quantities

How to calculate hops quantities

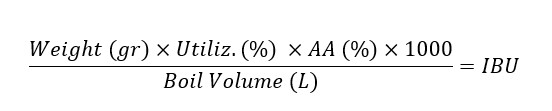

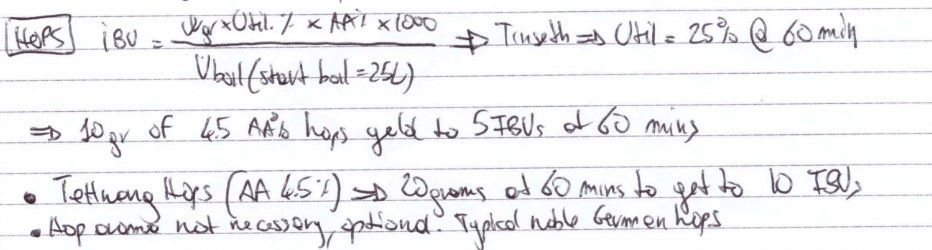

A similar rationale applies to the hops. We are going to employ the Tinseth formula (with metric units):

Utilization is determined by the timing of hop addition. It is reasonable to say that utilization value is:

- 25% for 60 min additions,

- 15% for 15 minutes additions,

- 0% for 5 minutes additions.

The boil volume is the starting boil volume (in this case, 25 liters).

Considering hops with 5.0% AA, we get that:

- 10 grams of hops at 60 minutes contribute 5 IBUs,

- 10 grams of hops at 15 minutes contribute 3 IBUs,

- we can consider 0 the IBUs for the contribution at 5 minutes,

- dry hopping does not contribute with any IBU.

When utilizing high-alfa-acids hops (like as Chinook in an IPA), use 10% AA and just twice the above figures.

Using this framework, you can calculate hop quantities during the exam without having to memorize them.

For non-hoppy beers that require a single 60-minute addition (such as lagers, Weissbiers, and Tripels), just use a 5.0% AA hop, divide the target IBU by 5, and multiply by 10 (or just multiply by 2) to get the hop quantity. For example, a Tripel with 20 IBU requires (20/5)x10 (or 20×2) = 40 grams of any 5.0 AA% hop @ 60 minutes.

For hoppy beers, utilize g/L as a starting point for late boil additions, calculate their IBU contribution, and close the gap with a 60-minute addition.

For example, a Double IPA needs 75 IBU. Adding 6 gr/L, which is a common number in that type of beer, yields 6g x 20L (liters in the fermenter) = 120 grams of late boil hops. Divide them equally between a 60-gram, five-minutes addition (0 IBU) and a 60-gram, 15-minute addition. Using high-alpha-acid hops (10% AA), each 10 grams of hops added at 15 minutes from the end of the boil contributes 6 IBU. 60 grams @ 5 mins will then yield 36 IBU.

Fill in the 75-36=39 IBU gap with a 60-minute addition. At 60 minutes, every 10 grams of a 10% AA hop yields 5×2=10 IBU, or 1 IBU per gram. We’ll then need 39 grams of hops @ 60 minutes.

To sum up, here is the hopping schedule for a Double IPA (75 IBU, 10% AA hops):

- 39 grams @ 60 min (39 IBU)

- 60 grams (3 g/L) @ 15 minutes (36 IBU)

- 60 grams (3 g/L) @ 5 minutes (0 IBU)

Dry hopping is required, but it’s easy to add. It is easily calculated as a pxq; typically 8-10 g/L for a Double IPA, taking into account the amount of beer in the fermenter. Once the fermentation process is complete, simply add 8×20=160gr of dry hops to the fermenter if it holds 20 liters of beer. It might be more intricate than that, but for the purposes of the exam, this is sufficient.

With a calculator on hand, it is quite easy to do the math. Of course, it is far easier with a Weissbier than with a Double IPA which requires more hops. The Weissbier, on the other hand, necessitates a more complicated brewing process with a single decoction.

I was lucky enough to get a Weissbier recipe that calls only for a 60-minute hop addition. Here is my exam answer for the hop component. Don’t forget to add a line to explain why you chose the hops.

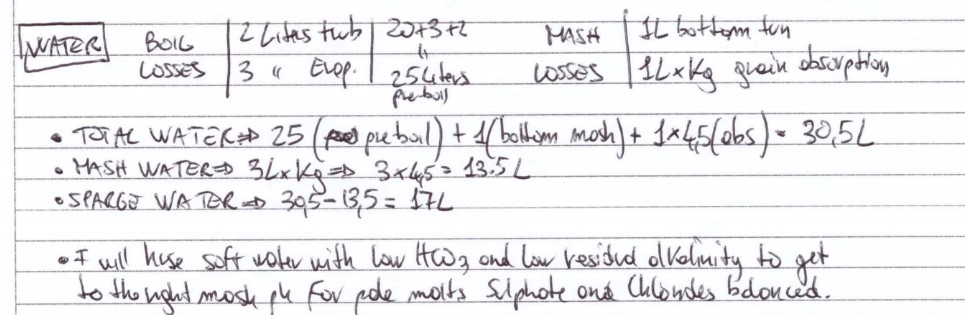

How to calculate water quantities

The best approach is to start from the volume in the fermenter and work your way backwards, considering:

- 2 liters of trub in the boil pot,

- 3 liters evaporation during the boil,

- 1 liter left behind in the mash tun,

- 1 L x Kg wort absorbtion by the grains after the mash.

Once the initial water quantity is calculated, use 3 L x Kg in the mash and the rest as sparge water. Don’t forget to add a line to explain how you’d treat the water.

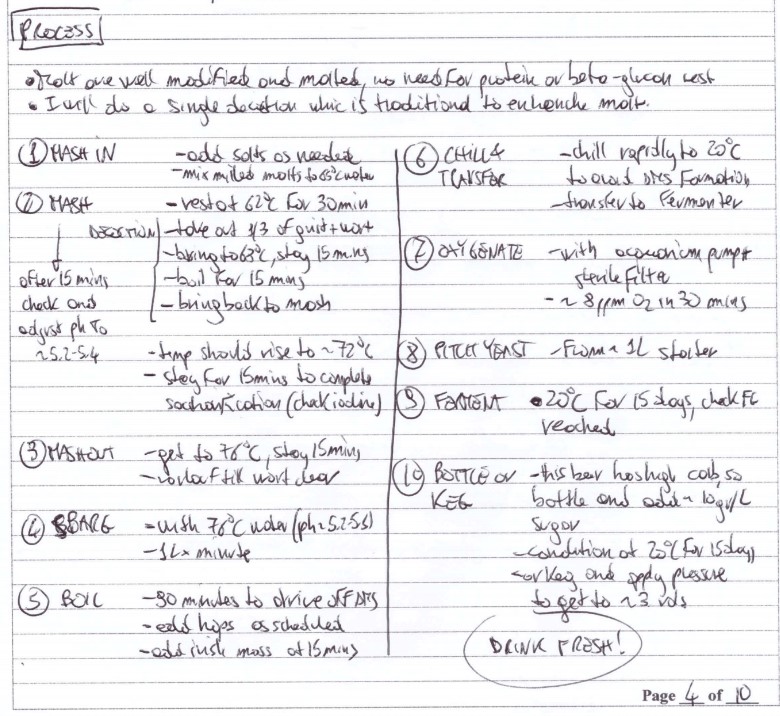

Describing the process

I diveded the whole process in 10 steps:

- Mash-in

- Mashing

- Mashout

- Sparge

- Boil

- Chill & Transfer

- Oxygenation

- Pitching the yeast

- Fermentation

- Bottling or kegging

Apart from the beers that usually require a decoction to boost the malt flavour (single decoction for the Weissbier and the Marzen, double decoction for the Czech Premium Pale Lager), the other ones follow the ten steps listed above.

Always specify that you won’t need additional rests (like the protein rest) because the malts are well modified. The Irish Stout is made using unmalted barley, but at 10%, it does not require any additional rest.

Decoction is easy to describe:

- take out 1/3 of the grist

- keep at 68°C for 15 mins

- bring to a boil and boil for 15 mins

- take it back to the main mash

It is important to stick to the 10 points listed above to avoid forgetting any step. Here is my answer for the Weisbeer production process:

Thank you for your article. but i found a lot of digit wrong.

1. the target par.

for example, the og you set for irish stout 1045 , american ipa 1055 , tripel 1070 are out of the range by the style guideline. range are respectively 1036-1044, 1056-1070, 1075-1085.

2. the hop calc.

with the formula: weight (gram) * utiliz (%) * AA(%) *1000/ boil vol = IBU

10g 4.5% @ 60 min would be 10*0.25*0.045*1000/25=4.5, you can round it up to 5. fair.

but for 15 min: 10*0.1*0.045*1000/25=1.8, that’s way off 3 IBU you’ve suggested.

i would use 5% AA hops. and set ult rate as 25% @ 60 mins, and 15% @ 15 mins.

that 10g hops would yield your suggested 5 ibu and 3 ibu respectively.

Thank you very much, Simba.

You’re right, the calculation for the 15-minute boil additions looks wrong. It must be a typo left over after I changed the AA% from 5% to 4.5% (as you suggested). I made the correction it in the post.

As for the OG of the styles, that slight shift is intentional so that I could group the recipe by OG and make them easier to remember. Nobody is going to heavily penalize an exam for getting the OG off by one or two points in the recipe question, as long as the recipe is solid.

My approach to this exam is simplification, because there are too many things to remember, and it would be impossible—at least for me—to memorize everything.

Thanks for the comment!

Thank you Frank! Your article is very helpful.